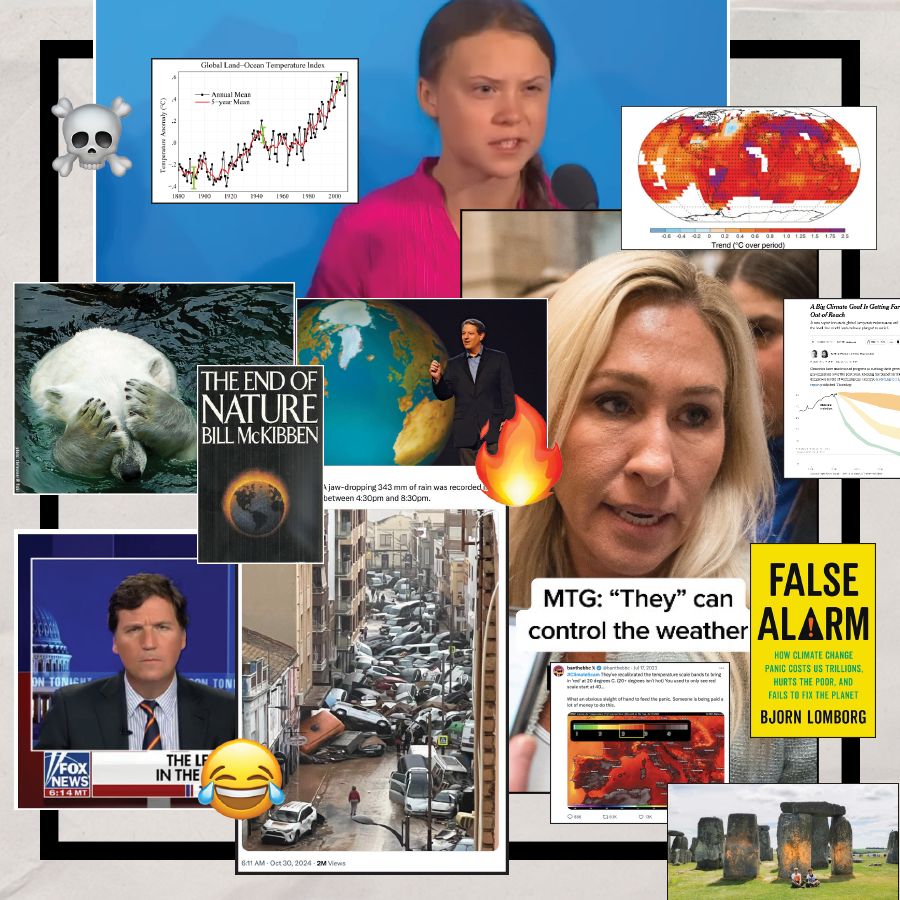

Up a narrow street in the Spanish province of Valencia, dozens of vehicles lay piled up like twigs after a storm. A year’s worth of rain had fallen on the coastal region in just eight hours, flooding towns and killing more than 200 people who had little warning of the apocalypse that was coming.

Early analysis suggests that global warming increased the likelihood and intensity of the extreme downpour, caused in this case by clashing warm and cold air over the Mediterranean Sea. In Paiporta, a town where at least 60 people died, residents digging themselves out of the devastation hurled mud from the storm at the king and queen of Spain who came to pay a visit, screaming out “killers” as a balm to their impotence and grief.

If a picture is still worth a thousand words in our hyper-visual societies, then these fragments of environmental destruction, and those demanding accountability, represent powerful ammunition in the climate-messaging wars swirling around us.

While outright climate denialism is waning as the direct evidence of global warming mounts around the world, new and more pernicious forms of denial are gaining ground. The election of powerful climate skeptics in 2024 – including Donald Trump, whose new energy secretary is a former fracking CEO who has talked up the benefits of a warmer planet and who just pulled the United States out of the Paris climate accord – shows just how fragile the gains made are.

Last year was exceptional for global democracy. More voters than ever in history headed to the polls in at least 64 countries, representing nearly half the world’s population. That’s why the “super election year” was also considered crucial for climate change – a chance for electorates to install leaders who could shepherd the delicate decisions required to drive down our planet-heating emissions. And yet, climate concerns far from defined those votes, suggesting that the magnitude of the problem still eludes us.

With 2024 going down as yet another hottest year on record, some scientists call the international target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels “dead as a doornail,” while the United Nations considers it to be “still technically possible.” Setting aside that abstract figures such as these mean little to the average person, the prescription depends on a massive mobilization to cut greenhouse gases, led by the industrialized G20 nations that have most contributed to warming.

Yet even at the world’s largest annual climate talks, the messaging has grown increasingly murky, muddied by fossil fuel interests and, as UN climate chief Simon Stiell put it, a mix of “bluffing, brinkmanship and pre-meditated playbooks.”

So where do we go from here? What’s the story we should be telling about climate change to produce concrete action that staves off its worst effects? With increasingly polarized public discourse, rampant disinformation and a democracy deficit driving a wedge between leaders and the communities they lead, can messaging make a difference?

1.5 degrees of separation

“What we know is we can get people to care.” That’s Sergio Velasquez-Rose, head of strategy, insights and analytics at the Potential Energy Coalition, a non-profit, non-partisan alliance of marketing agencies trying to shift the conversation on climate change.

Polling suggests that much of the global public does, in fact, understand what is at stake.

The largest stand-alone public opinion survey, known as the People’s Climate Vote, took the temperature of 77 countries – representing 87% of the world’s population – in 2024. It found that 86% of respondents want countries to work together to find climate solutions, even if they disagree on other issues such as trade and security. Eighty percent want their communities to strengthen their climate commitments, and 71% want their countries to replace coal, oil and gas with renewable energy quickly or somewhat quickly. A survey by Potential Energy of 23 countries came to a similar conclusion: more than three-quarters of respondents want governments to do “whatever it takes” to limit the effects of climate change.

This suggests that crafting a climate message that resonates shouldn’t be that hard. But it has been.

“We really see this as a major communication problem,” Velasquez-Rose says. “We have the policies, we have the solutions, we know what the problem is and how to address it – but we have not been able to connect with humans in the right way.” He adds, “We’re getting stuck in concepts.”

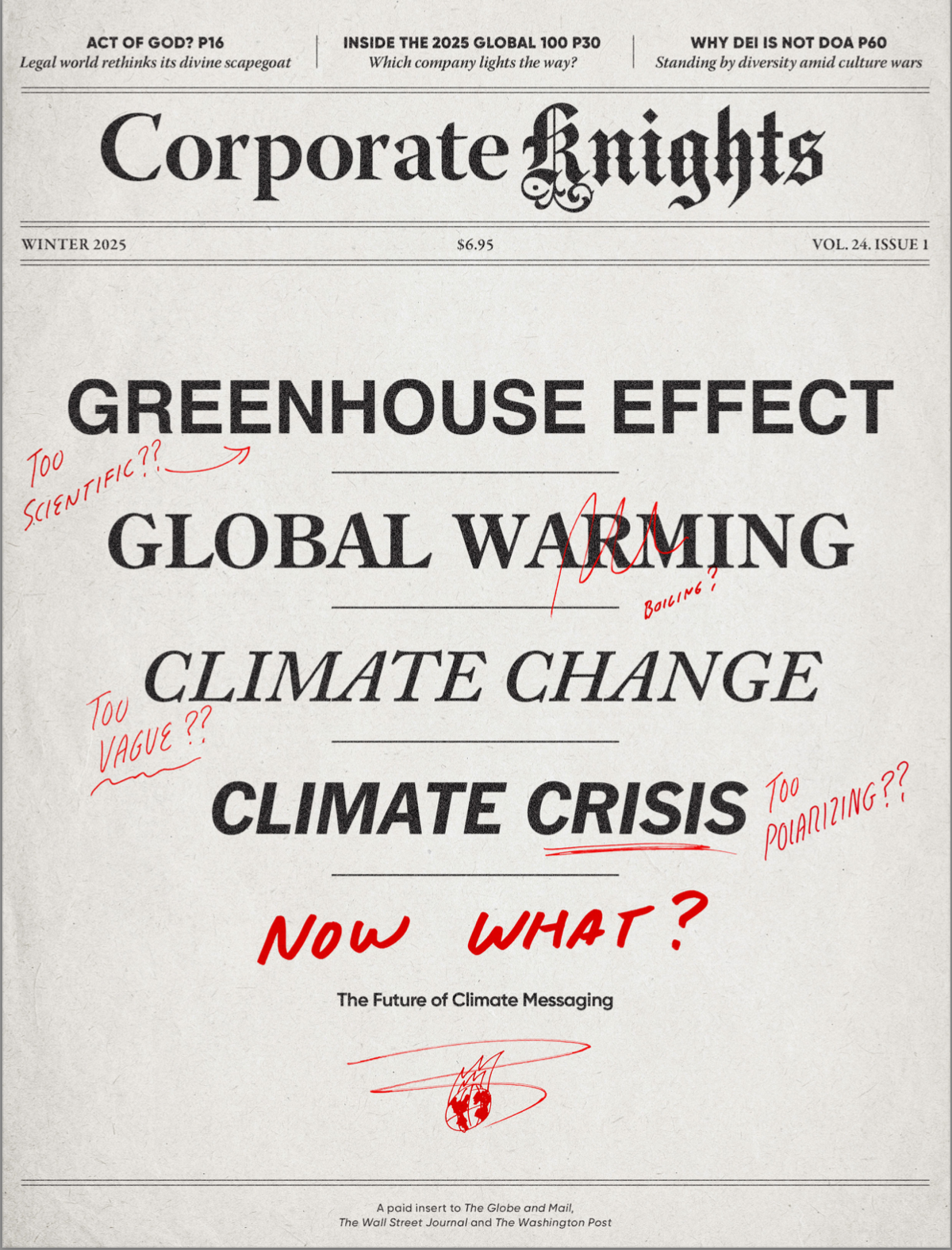

In its climate marketing guide called “Talk Like a Human,” Potential Energy lays out tips and traps – the latter of which this article has already fallen victim to. Words including “decarbonization,” “net-zero,” “anthropogenic” or “carbon footprint” don’t work. Instead, lean into pollution, overheating and extreme weather. Don’t exaggerate, it says – terms like “climate emergency” or “climate crisis” work much better with people who are already alarmed but not with people who aren’t, Potential Energy has found. Even something like “fight climate change” has pitfalls, its research has discovered. Instead, “fight pollution” is far more effective, accurate and a framing that people are already familiar with.

We talk to people’s heads, but we forget to talk to people’s hearts.

—Mark Hertsgaard, co-founder, Covering Climate Now

Too often, climate change coverage is locked in scientific abstractions, such as 1.5 degrees or parts per million, notes Mark Hertsgaard, who co-founded Covering Climate Now, a partnership of now more than 500 media outlets (including Corporate Knights) that share content and expertise over how to cover climate change. Most people don’t know about the Paris Agreement, let alone the significance of 1.5°C.

“We talk to people’s heads, but we forget to talk to people’s hearts,” says Hertsgaard, who has reported on climate for 30 years, from 25 countries. When he launched Covering Climate Now five years ago, the goal was to break the “climate silence.” Through a collective effort that stretches beyond his organization, he believes that has largely been achieved. But coverage is still driven by the “weather story” and occasionally by climate change conferences, with little intersection with political and economic desks. “That reflects a misunderstanding, to put it mildly, of what climate change is and what it means: that this is an existential threat comparable to nuclear war and nuclear weapons, just on a different time frame,” he says.

India, for example, went to the polls in the midst of a ferocious heat wave in June that claimed the lives of dozens of election workers and set off protests about water shortages – but climate was hardly at the forefront for presidential contenders. A feedback loop was missed. “Had candidates talked more about it, then media would have talked more about it, and had the media talked more about it, candidates would have talked more about it,” Hertsgaard says.

Therein lies another issue: the messengers. The fact that politicians are currently the main communicators of climate action is a problem, Velasquez-Rose says, given their lack of credibility in large swaths of the planet. In the United States, which Potential Energy research shows has the greatest polarization on climate issues in the world, climate action is mostly associated with just one party, alienating those who support the other.

Before the pandemic, Greta Thunberg, the Swedish youth environmentalist, had hit a nerve, mobilizing millions of young people from Argentina to Iceland to skip school and join marches to demand greater action from their governments with her Fridays for Future movement. But by 2024, some of the most visible climate messengers were critical of climate policies: European farmers driving their tractors into cities, pelting police with beets and dumping potatoes in front of legislative buildings in a standoff that led legislators to roll back environmental policies on the fastest-warming continent on the planet.

“We need new voices to be the face of climate,” Velasquez-Rose says. He points to the success of a campaign they have run called “Science Moms,” which features scientists who are also mothers speaking about the impacts of climate change. In the five years since the campaign launched, it has increased support for climate policies by 20% among the target audience of moderate suburban mothers, Velasquez-Rose says. The Science Moms have credibility, and they are relatable, which is part of the secret sauce.

Climate messaging bubbles and the new denialism

It’s not just what is being said, and who is saying it, but how that messaging is being funnelled and funded. For decades, the right-wing media machine in the United States has been building a powerful amplification system that stretches across evangelical churches, radio talk shows, podcasts, influencers and YouTube streamers, with massive amounts of funding from oil and gas interests and beyond pouring into anti-climate messaging that spreads disinformation like wildfire. “Nothing like that exists on the left,” Hertsgaard says. “Instead, there is a mainstream media that is still trying to play by the old rules that we’re going to be so-called objective and we’re not going to take sides. We sure as hell should be partisan as hell on behalf of the truth.”

New fronts have also opened in the messaging wars that are reflected in a reframing of who bears responsibility. Richard Brooks, the Toronto-based climate finance director of Stand.earth, an environmental organization, notes the slippery shift from big banks. “There is this term that we keep hearing over and over again, which is that the energy transition that needs to happen has got to be ‘orderly’ – I’m going to put that in quotes,” he says. “And that is code for ‘We will stay invested in oil and gas companies.’ It will continue to be business as usual.”

Since the Paris Agreement, Canadian bank investments in fossil fuels haven’t significantly changed, Brooks notes, with the “Big Five” banks funnelling nearly $1 trillion into the industry between 2016 and 2023, according to Stand.earth. “Slow-walking on climate action is really the new climate denialism,” he says.

Brooks is part of a wave of longtime environmental activists who have shifted away from climate-messaging campaigns that try to get the public on side and instead have set their sights on the finance sector, fuelled by the belief that money is the message. Some, like the founders of Investors for Paris Compliance, are now working as shareholder activists, directing their messaging to hold Canadian publicly traded companies accountable to their net-zero promises. A number of environmental groups have established climate finance arms, including Stand.earth, which calls out inconsistent messaging from banks that claim to be net-zero aligned while still financing fossil fuels.

“We need to challenge any corporate leader [or] CEO of a bank or pension fund who says we need to go orderly on this and slow,” Brooks says. “There’s nothing orderly about wildfires forcing thousands to evacuate [or] Toronto, the financial centre of Canada, flooding twice this summer.”

From ‘greenwashing’ to ‘greenhushing’

Fear of getting caught in the crosshairs of the climate-messaging wars has contributed to a growing number of companies going quiet. A Republican-led backlash against corporate climate policies, under the banner of ESG (environmental, social, governance), has given rise to “greenhushing” – rather than aggrandizing environmental initiatives through “greenwashing,” companies are shying away from publicizing their green efforts.

“In a polarized political environment, communicating about climate can feel risky for a publicly-traded company,” writes the Potential Energy Coalition, which teamed up with the We Mean Business Coalition to develop a new messaging guide for businesses. Across the globe, research shows that consumers want companies to reduce planet-warming pollution and invest in clean energy. In fact, they are more likely to spend their money on, speak well of and want to work for corporations that do so. The key, Potential Energy has found, is to frame climate action around materiality – not morality.

“One thing is the messaging, the other thing is the business reality,” says María Mendiluce, CEO of We Mean Business and co-founder of the Women Leading on Climate coalition. “We see that the business community across the board is moving to clean energy because it makes business sense.” Still, language matters, she says. “In general, it’s quite simple: simple messages that people understand, that they can relate to.”

“I think the left has been very good at complicating things to a level that many don’t understand and disconnecting with the base, with people who may not have that level of understanding of something that is really complex,” Mendiluce says. “We talk about ESG. And people are like, what is this? Even for me, and I come from the energy world.”

One person who is adept at distilling a message so it resonates with a wide audience is once again president of the United States. The Democrats may have shied away from making climate change a focal point of their campaign, but Donald Trump used it. In the battleground state of Michigan, the Trump campaign ran ads that demonized the electric vehicle industry and cut to the heart of U.S. sensibilities about personal freedom and government overreach. “Kamala Harris wants to end all gas-powered cars. Crazy but true,” one commercial said. “Michigan auto workers are paying the price. Massive layoffs already started. You could be next.”

The climate change message has become so toxic to right-wing voters that some advocates for climate action believe the key is finding approaches that sidestep the topic and engage on different terms. For Joe Sacks, a Democratic political strategist, that means finding “friendlier terrain.” He is executive director of the EV Politics Project, a venture launched by EV-owning Republicans “frustrated by the growing EV bashing” and looking to foster more productive discussions around electric vehicles. His group found that US$35.5 million was spent nationwide on EV advertising during the presidential campaign. Some 94% of that money was spent in Michigan, the automotive heart of America, and the vast majority of the messaging was anti-EV.

Sacks thinks that Democrats should stop messaging along climate lines when it comes to EVs. “That’s just not how this is going to work. We need to find messaging that brings people in, that meets them where they are,” he says. Right now, he says, that message needs to revolve around manufacturing jobs. “Jobs that you often don’t need to get a college degree for, jobs that are often unionized, and when they’re not unionized they still pay really well, jobs that are spread across this country.”

Democracy deficit

Tyrell Gittens, a climate change reporter in Trinidad and Tobago, agrees that the key is speaking to people in terms that hit closer to home. Issues like inflation or the success of their crops remain top of mind for many on his island nation, but the volatile climate’s role in that is still not clearly understood by many. “People want to understand; we have to meet them where they are,” he says. “An informed citizenry will create political will.”

Inés Camilloni, a climate scientist in Argentina, notes a whole host of economic and geopolitical factors well beyond the scope of communication that make progress on tangible climate action complex, and, certainly, too slow. But “we have progressed.” And she credits messaging with helping usher in cultural transformations, including in places like her home country, where young people inspired by Thunberg helped push the government to enact new environmental legislation. That was, however, before the election of the current president, Javier Milei, a strong ally of Trump who echoes his denial that climate change is human-caused. In November, Milei pulled his delegation from the COP29 discussions and then revealed he was reconsidering Argentina’s place in the Paris Agreement, a move that raised the spectre of other countries following suit. “We are in uncertain times,” Camilloni admits.

The biggest motivator

For Hertsgaard, there are important levers still to be pulled in the messaging battle. “We have to be talking about solutions – not just what’s wrong,” he says. And drawing more attention to the gap that exists between what people say they want from their governments on climate action and what governments are doing.

The research is already painting a pretty clear picture of what works, Velasquez-Rose notes. Protecting one’s health and protecting our homes and families against extreme weather performs far better as a motivator for action against climate pollution. But fear versus hope is the wrong debate. The biggest motivator is protecting what we love.

“The thing that ultimately gets us, that really core human truth, is protecting the future for the next generation,” Velasquez-Rose says. “When we think about communicating, we need to think about the humans. I can’t reiterate that enough.”

Natalie Alcoba is a Buenos Aires-based journalist and senior editor at Corporate Knights.