If there is a limit to how far populist politics can detach from the concrete realities of a warming planet, those living under the aspirational authoritarianism of President Donald Trump are well positioned to find out.

Trump’s second administration has frozen billions in funding for research and laid off thousands of people working at science agencies. The president’s loyalists are enforcing a keyword-directed censorship campaign to expunge research tied to culture-war hobgoblins like diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility. Also targeted for suppression: the study of climate change – the basic physical process of global warming that has been accurately understood and described since the early 19th century.

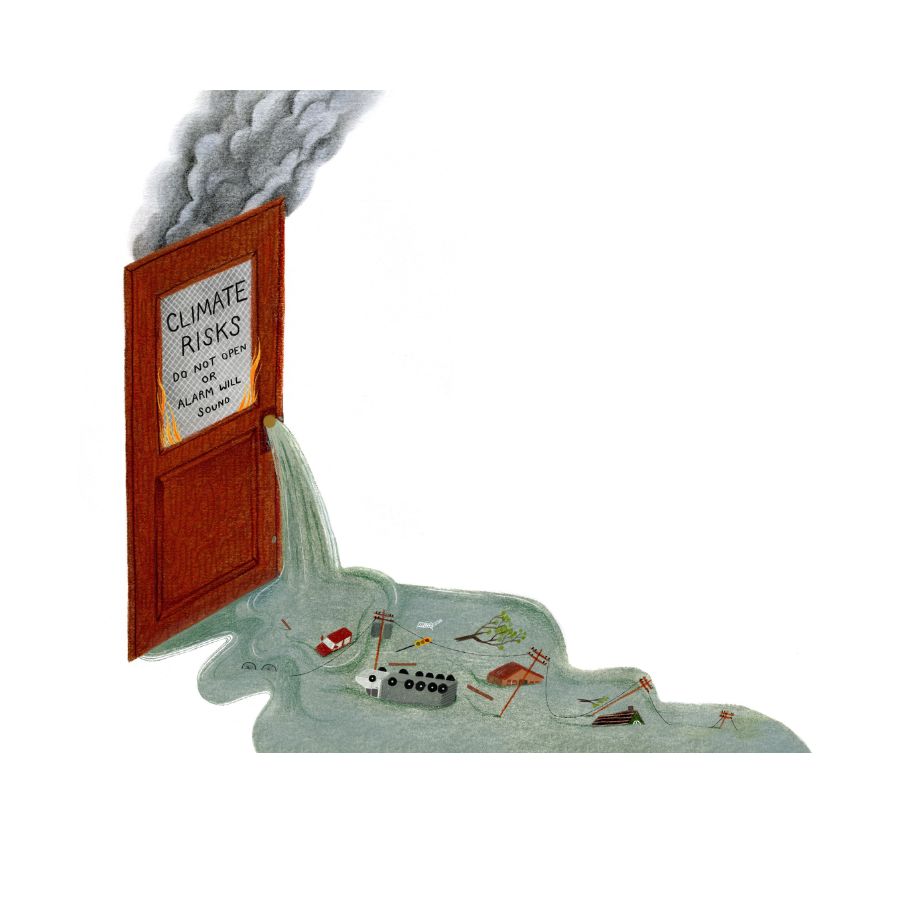

Ideologues and allies of the oil and gas industry may find it convenient to suppress two centuries of atmospheric science, but many large investors are finding such denialism increasingly unworkable, and for reasons that are not “woke” by any stretch. Simply, the fiscal threats posed by climate change and the energy transition are emerging more and more clearly into view.

The emergence of climate risk reporting

Among the various political, social and technological revolutions now unfolding in our polarized world, there is one that promises to more effectively neutralize the anti-science agenda and satisfy investors along the way: mandatory climate-risk disclosure. This clumsy four-word phrase is the closest thing to shorthand for the suite of international regulations that require companies to report their exposure to the material financial risks from climate upheaval.

Climate-risk reporting isn’t new. Various forms of voluntary disclosure have been around for decades, used by companies that want to get a leg up in the clean economy and appeal to sustainable investors. But the lack of common standards and real accountability has created uncertainty and enabled greenwashing. Which is why large jurisdictions like the European Union and Australia have made it compulsory, and many others are moving inexorably in that direction.

Mandatory climate-risk disclosure is short on cheerleaders. Opponents see it as red tape and a constraint on competitiveness, while many climate campaigners say it’s the bare minimum. But compulsory risk reporting has the potential to provide a real propellant to the energy transition, because it is the main vehicle by which climate scientists are getting their message across in the place that sets the pace for decarbonization: the global financial market.

Enormous efforts are underway by Big Oil’s political servants to halt this transformation in the finance sector, but despite the delays, the demand for credible climate-risk reporting is not going away, especially as those risks continue to become realities. As realism gains ground, denialism’s days are numbered. There’s too much money at stake. The question, as always, is whether the change will happen fast enough.

A sea change in the financial sector

To think about how the financial sector is responding to climate risk, it’s useful to set a frame of reference from your own understanding of what to expect on a warming planet, and how that has evolved. Whether you accepted the science of climate change decades ago or tend to see it as a hobbyhorse for left-wing alarmists, your feelings have no doubt changed as the drumbeat of droughts, heat waves, storms and floods grows louder. Think about how you felt 10 years ago compared to how you felt watching Los Angeles burn in January, during what was supposed to be its rainy season. Now take that trajectory and extend it forward: five years, 15 years, 50.

Or just find a temperature graph of the past century, put your finger on the bottom left corner, and move it rightward. Keep going when you get to the end.

Something like that is happening in the financial world, albeit with more complexity and jargon. The shift began with the Paris Agreement in 2015, when the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was created. The focus of the TCFD has been to guide how companies generate useful information about their impact on the climate, but the utility goes the other way too: showing investors how climate change may affect companies.

Most countries in the world are committed to transitioning their energy systems away from fossil fuels. It’s the financial impacts associated with that transition that shift value assumptions and value projections.

– Kyra Bell-Pasht, Director of Research and Policy, Investors for Paris Compliance

The creation of the TCFD began the process of financial institutions “starting to wrap their heads around the fact that their climate risk isn’t the energy they use in their brick-and-mortar locations or how much gas they use driving to work,” says Kyra Bell-Pasht, the director for research and policy at Investors for Paris Compliance, an organization that seeks to hold Canadian companies accountable to their net-zero commitments.

The TCFD guidelines drove home the realization that responding to climate isn’t just a feel-good exercise to create fodder for marketers. The framework helped more institutions recognize that “the financial risk they’re being exposed to is through the financial activities they’re undertaking – the core of their business,” Bell-Pasht explains.

The work of the TCFD paved the way, in 2021, for the launch of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), an international cohort of banks committed to transitioning their financed emissions. At its peak, the NZBA included 140 banks representing around US$64 trillion in assets. For the first time, large institutions were publicly acknowledging the material financial risk to their shareholders from climate change.

The NZBA unravelled after Trump’s re-election, with most of the member banks exiting the alliance over a period of a few months, seemingly in response to Republican pushback and lawsuits to prevent investment managers from considering environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors in their decisions. The banks say they have not abandoned their net-zero commitments, and certainly all the economic drivers – and hazards – still apply.

What are the risks?

In its 2025 global risk report, the World Economic Forum warned that extreme weather events, biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse are all expected to worsen in the next 10 years. The earth is on the cusp of crossing multiple climate and ecological tipping points, each of which would impose destructive, self-reinforcing loops with severe consequences for food and water security, public health and political stability.

For example, scientists now warn that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation – the system of currents that circulates water and redistributes heat in the Atlantic Ocean – is at “significant risk” of collapse in the coming decades. In that scenario, modelling by researchers at the University of Exeter suggests that roughly half of viable land worldwide for staple crops like wheat and maize would disappear.

For example, scientists now warn that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation – the system of currents that circulates water and redistributes heat in the Atlantic Ocean – is at “significant risk” of collapse in the coming decades. In that scenario, modelling by researchers at the University of Exeter suggests that roughly half of viable land worldwide for staple crops like wheat and maize would disappear.

This and many other risks from climate change have led the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries in the United Kingdom to forecast a 50% loss in gross domestic product for the global economy between 2070 and 2090, if we continue with business as usual.

But as the retreat of property insurers from huge swaths of at-risk real estate demonstrates, the threats aren’t just far away – they’re near-term, too.

This perilous landscape points to one basic category of threat that businesses face and that investors might want to know about: physical risks, such as losing assets to storms and fires, or supply chain disruptions from geopolitical turmoil over resource competition and mass migration (see: Trump’s tariffs).

But there is another category of risk that speaks to financial actors more directly: “transition risks” for carbon-intensive companies, especially those with no plans to divert from business as usual. These companies – and the investors who buy their securities – are on a collision course with the inevitable.

If you’re a pension and you’re going to spend billions on a new asset, if you don’t have a climate expert in the room throughout the whole process, you’re crazy.

– Adam Scott, Director, Shift Action for Pension Wealth and Planet Health

Policies, markets, supply chains and technologies are all evolving and adjusting to the reality of climate change, and businesses that fail to keep up with these developments risk losing customers. “Most countries in the world are committed to transitioning their energy systems away from fossil fuels,” Bell-Pasht explains. “It’s the financial impacts associated with that transition that shift value assumptions and value projections.”

There are other important risks for companies and investors to consider, too, and legal liability is chief among them. Lawsuits against high-emitting companies are multiplying, and a host of favourable rulings are sparking optimism among climate activists – and fear in the oil and gas sector.

The global outlook on climate risk disclosure

Mandatory climate disclosures have already come online in several countries and are set to launch soon in others, while more countries are moving inexorably in that direction. Established in 2021, the International Sustainability Standards Board launched a set of global standards in 2023 that have been instrumental in facilitating worldwide adoption.

The key jurisdictions where these rules already apply include Australia, where new mandatory disclosures came into effect for 6,000 large companies in January, and New Zealand, which now mandates disclosures for large companies, insurers, banks and investment managers; California passed a law last September that requires companies doing “significant business” in the state to disclose greenhouse-gas emissions data and climate-related financial risks; and the EU has the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which is the most advanced regime so far, despite recent erosions.

Canada doesn’t yet have federally mandated climate disclosure obligations for corporations, but in December the Canadian Sustainability Standards Board published a non-binding disclosure framework that lays the groundwork for future obligations. Meanwhile, Canada’s Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions has implemented climate-related disclosure requirements for the banks and pension funds that it supervises.

Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan all have climate disclosure schemes that are set to expand. Brazil’s mandatory ESG reporting regime for publicly traded companies will come into effect in 2026. China, too, has established requirements for sustainability reporting. And elsewhere around the world, countries are developing their own disclosure frameworks, such as South Africa, Kenya and India.

Setbacks aplenty, but demand is fixed

There are, of course, plenty of mixed signals. In February, the European Commission introduced an omnibus bill that aims to dramatically reduce the requirements and the number of companies affected by CSRD to such a degree that labour unions, environmentalists and sustainable investors say the legislation has been effectively gutted. Companies with more than 1,000 employees will still have to report (see p. 10).

RELATED

As banks backslide on climate, Canadian shareholder groups demand reforms

To boost competitiveness, Europe proposes slashing key climate rules

Do ‘act of God’ clauses still work in the era of climate change?

In the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission had adopted new mandatory climate disclosure rules in March 2024, citing investor demand. These were met by a suite of legal challenges. To the surprise of no one following Trump’s election, the SEC halted its defence of the rules in February. Mark Uyeda, who was appointed acting chairman of the SEC in January, said in a statement that the benefits don’t outweigh the costs.

But the delays and setbacks might not be as devastating as they seem. “The signals to the market are very important,” Bell-Pasht says. “Even if it’s a few years off, if companies know that it’s coming, they will start receiving increased demand from their investors to say how are you getting there.”

Likewise, many companies operate internationally, notes Hemanth Setty, founder of Zero Circle, a sustainability reporting platform based in New York: “They’re not going to change their policy based on one country’s decision.”

New opportunities, more contradictions

Large investors are looking at the combined business risks from stricter regulations, supply chain disruptions and market shifts toward sustainability, and it makes them want more information, not less. “Corporations are staffing up,” Bell-Pasht says. “There’s a huge hunger for expertise on this stuff.”

Pension funds in particular, with their longer horizons, are more naturally inclined to heed climate science and more likely to employ climate-risk experts in-house. “If you’re a pension and you’re going to spend billions on a new asset, if you don’t have a climate expert in the room throughout the whole process, you’re crazy,” says Adam Scott, director of Shift Action for Pension Wealth and Planet Health.

In February, one of the largest pension funds in the United Kingdom, The People’s Pension, pulled £28 billion in assets from the U.S. asset manager State Street over its poor record of tackling social and environmental issues. The pension transferred those funds to management companies with a stronger sustainability focus.

But the push for climate reporting can create some dizzying contradictions. The global head of J.P. Morgan’s climate advisory unit, Sarah Kapnick, wrote in February that success depends on the firm’s ability “to integrate climate considerations into daily decision-making.” Kapnick, who was the chief scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is an example of climate scientists gaining influence in financial institutions. At the same time, JPMorgan Chase – the large banking conglomerate that operates J.P. Morgan for its investment business – is the world’s top funder of fossil fuels. Clearly, those climate considerations are not yet reaching the top to a meaningful extent.

Just as large investors are staffing up, big companies are reaching out for climate services and analytics to help them complete their reporting. Service providers are piling into this gap and jostling for market share as more and more companies start to make climate disclosures, in what has been called a “climate intelligence arms race.”

But many of these providers have been criticized for lack of accuracy and validation, and for making claims that aren’t scientifically rigorous. As they are finalized and implemented, mandatory disclosure regimes will impose some order on the Wild West of climate services providers.

What comes next for climate disclosure

At the end of the day, mandatory disclosures are the foundation, not the destination, Shift’s Scott says. Relative to phasing out fossil fuels and transitioning to a clean energy economy, reporting climate risks is “the first baby step.” Most pension funds are ahead of the curve, but “a lot of them are still partway through that process of actually coming to grips with what this means.”

Banks, too, are still at the beginning of their journey. “We do believe that mandatory disclosure rules are what’s going to be the difference between what we have today and a full net-zero transition plan of a major bank or insurer,” Bell-Pasht says.

For now, Scope 3 emissions – from fossil fuels burned up and down the supply chain or by users of the product – have been left out of the reporting regimes, but they need to be included, climate advocates say. “Everybody complains: ‘They’re not my emissions,’” Scott says. “For an investor, this is the most crucial category. This is where you see transition risk.”

To make this work, companies need to start seeing more carrots than sticks, Setty says. Zero Circle walks companies through the reporting process to give them better access to things like ESG funds and sustainability-linked loans. “It has to be tied back to incentives, opportunities and growth.”

Mark Mann is a journalist and editor at Corporate Knights. He is based in Montreal. Explore his portfolio of essays and reporting here.

The Weekly Roundup

Get all our stories in one place, every Wednesday at noon EST.