In the days following Donald Trump’s fateful ballot box victory in November, environmental advocates the world over stumbled around shellshocked, feeling the ear-splitting pressure change of a bomb dropped on climate progress months before they’d ever see the fallout. As grief and fear spilled onto social media feeds, one climate leader held space for hope.

“There is an antidote to doom and despair,” the architect of the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change posted. “It’s action on the ground, and it’s happening in all corners of the Earth.”

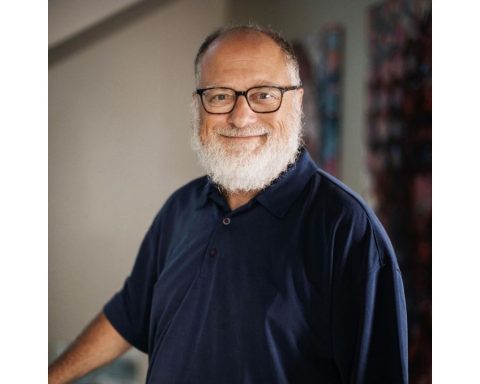

Now a decade since Christiana Figueres accomplished the Herculean task of getting 196 countries to put their differences aside and adopt the accord, the former United Nations climate chief and long-time Costa Rican diplomat remains deeply attuned to the emotional toll the climate crisis has taken on those advocating for action. “The pain of the climate communities is at an all-time high,” she tells Corporate Knights on a call from her coastal home in the Guanacaste province of northwestern Costa Rica. She knows their climate anxiety well. “I used to wake up every single morning with an alarm clock ringing in my gut, because scientists are screaming from the rooftops that we have deadlines right in front of us . . . and we all know we are running out of time.”

That “pre-traumatic stress disorder,” as she calls it, is only intensifying as administrations in the United States, Argentina and even the green poster child of Costa Rica brandish chainsaws to climate regulations, while Trump is “breaking the very bones of society.” And yet somehow, Figueres manages her trademark mix of “outrage and optimism” (which, by the way, is the name of her popular climate change podcast) from a much more Zen space. Now she’s working on sharing her secret to alchemizing our collective pain into personal and planetary resilience with thousands of climate leaders, at a time when they need it most.

By the time Figueres took on the role of executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change in 2010, she had been working as a diplomat, renewable-energy advocate and international climate negotiator for three decades. Figueres was in the thick of dealing with the pressures of preparing for the Paris Agreement in 2013 when “out of the clear blue sky” her 25-year marriage fell apart. Overwhelmed by grief, she was wracked with suicidal thoughts, until, she says, she discovered the teachings of Zen master and long-time peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh. “It was really – I mean literally – a lifesaver for me.”

She remembers reading and re-reading his calligraphy that said “The tears of yesterday have become rain.” “Slowly I began to understand that I had a choice about the pain that was overwhelming me.” That pain could become the “chrysalis for learning and growth,” she explains – “the mud needed for a lotus to grow.”

Hanh was known as the “father of mindfulness” in the West, but to Figueres, he soon became her spiritual father, without whom, she says, the Paris Agreement may not have happened. For those keeping count, that gives Figueres two high-profile dads. Her birth father, José Figueres, was equally formative in shaping her brand of climate diplomacy: the coffee grower turned revolution leader served three elected terms as president of Costa Rica and is considered the founder of the Central American nation’s democracy.

Is the energy that I bring to myself, to others, to this work stemming from grief, pain and despair, or am I transitioning my energy to one that stems from love and care?

— Christiana Figueres, co-founder, Global Optimism, and former UN climate chief

Before the 95-year-old monk’s death in 2022, Figueres had begun working with the monastics at Plum Village, Hanh’s global community of mindfulness centres/Buddhist monasteries, to share his teachings, through week-long meditation retreats for leaders in the climate and biodiversity space and a seven-week online course for broader reach. During Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet (ZASP), the virtual course based on Hanh’s bestselling book of the same name, a dozen monks, nuns and Zen community leaders – including Figueres – led a cohort of 1,400 participants from 70 nations through a tumultuous fall season.

ZASP students – myself among them – ranged from activists and scientists to sustainable business consultants and concerned citizens. We were shown a number of daily practices to ground our nervous systems, including mindful breathing and walking. But the teachings go beyond the usual mindfulness techniques that have burgeoned on meditation apps for the last decade. Daily talks and short meditations are designed to cultivate a deep reverence for and sense of interconnection or “interbeing” with the earth, an approach that was quintessential to Hanh, who was exiled from Vietnam for his activism during the war. At Plum Village, Europe’s largest Buddhist monastery, Hanh established his own brand of “engaged Buddhism” rooted in caring for the earth. It’s not just about quieting the mind; the course encourages us to slow down to cultivate the mindset, openness and understanding needed to work collaboratively to address the climate crisis.

Getting out of our judgment box

At the course’s first sharing group two days after the U.S. election, participants are guided to break off into groups of four and practise deep listening – listening without interrupting or commenting. Admittedly, it’s tough not to jump in and turn it into a venting session about Trump’s win. But as Figueres has reminded us in her weekly talks, with practice, deep listening is a gift we can give loved ones and a powerful technique that can transform our work in the world.

“What I love about the deep-listening skill that we are taught is the fact that it takes us out of our judgment box,” Figueres says. “If I’m in a conversation with anyone, my default is to bring my own prejudices, but when you enter into a conversation from that space, you already enter a dead conversation.”

Figueres confesses that during the last stretch of negotiating the Paris Agreement, she had to check her judgments at the door in conversations with governments that she disagreed with “from the bottom of my gut.”

“That’s where it got truly challenging for me, to be able to not react immediately but rather stay with my breathing, stay with my listening skills.” Instead of preaching at them, she decided to ask them each about their history, their concerns, their aspirations. Although every country started from a different place, their realities began to merge, she explains, when they each came to the realization that “those future aspirations boil down to a stable, safe planet” – without her needing to sermonize, she adds. “Once you touch the pain or the fear that is behind people’s words and actions, then you have a rich conversation that can move you forward.”

Today, she’s teaching the technique as an antidote not just to the polarization splintering societies, but also to the divisions within environmental communities that can, at times, descend into what she calls “circular firing squads.”

“How many times do we not agree with colleagues who are also doing the utmost to address climate change? So many activists, leaders, scientists, corporates, financial institutions, all of whom are working toward the same direction of decarbonizing the economy with a different view,” she says. “If we have the space within ourselves, the inner space to have these conversations from a sincere non-judgmental perspective, we actually are able to find common ground and move forward together.”

Damned if you’re doomed

Of course, Zen has its limits. All the compassionate listening and mindful breathing in the world won’t stop Trump’s administration from smashing environmental regulations and opening the floodgates to more drilling and tree-felling. What then? Remembering that the world is bigger than the United States is key, Figueres says, and that the clean energy transition is larger than one government. “Trump is not the be all and end all of everything.”

She says to look for tectonic shifts in leadership, from states, from other countries, and from companies. “The largest companies in the United States understand that this is going to be yet another four-year hiatus in efforts to decarbonize the global economy or the U.S. economy, but that four years is not eternity – it is four years,” says Figueres, who launched a coalition of CEOs, investors, mayors, governors, scientists and youth activists last June called Mission 2025, all inviting governments to ratchet up their climate action plans.

“These companies know that they actually have to plan much longer-term than four years, and they know that decarbonizing their products and services is the only path that they can follow because that is irreversible right now.”

Her work with Mission 2025 and Plum Village, along with her Outrage + Optimism podcast and other offshoots of her Global Optimism organization, all ultimately flow into the same river: Figueres is laser-focused on sparking mindset shifts, “radical collaborations” and new narratives that foster the urgent action needed on climate change.

It’s all part of an effort to “change the narrative in the way that I’m sharing with you now for us all not to succumb to this doomism and think that the world has come to an end,” Figueres says.

Admittedly, some days, she does find herself overwhelmed by pain and anger, knowing that millions of people are already losing their homelands, their livelihoods to climate change. “That moral injustice is unacceptable to me.” But as painful as it is for us to hear, for instance, a growing number of climate scientists warn that the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C is already “deader than a doornail,” Figueres says that focusing on failure only distorts reality. “The challenge is that we humans are programmed for a negative bias; we’re wired for always being vigilant about the threats. We’re not wired to be vigilant about opportunities.”

And that, Figueres says, is our personal responsibility as climate advocates. “I don’t need to worry about not being informed of the threats. Those are a tsunami that comes at me all the time. I do need to put energy and intention on being much more mindful and conscious of positive things that are happening. That’s how I balance. And that actually is more representative of reality,” she adds, pointing to the momentum behind wind and solar energy and the rise of EVs.

No mud, no lotus

During the last week of teachings, as with every week, Figueres reminds the Zen students “why this all matters.” She challenges us to mirror the change we want to see in our work and in the world.

“I’ve been reminding myself that yes, I do want policy changes at the level of governments and corporations, and I asked myself what policy changes am I operating with respect to my thoughts and actions? Yes, I do want to accelerate the energy transition, and therefore am I transitioning my own energy? Is the energy that I bring to myself, to others, to this work stemming from grief, pain and despair, or am I transitioning my energy to one that stems from love and care? Am I nurturing and caring for my own personal resilience so that I’m not in constant burnout mode?”

Seven weeks into the course, my own energy feels more renewable, though some days just following breaking news can still feel like an emotional mudslide. But as Hanh would say, ‘No mud, no lotus.”

“Lotus flowers only grow in ponds that have a muddy bottom,” Figueres tells students. “And that is the beautiful symbol of how we transform the mud in our life into lotus flowers. We can choose to be overwhelmed by all the mud ponds in our life, of which there are many, or we understand that every mud pond is precisely where the lotus flowers can grow and bloom.”

Adria Vasil is the managing editor of Corporate Knights and author of the bestselling Ecoholic book series.