In Fort Nelson First Nation, the remnants of a fossil fuel era that made oil barons rich are littered across the landscape. Orphaned oil wells punctuate the Dene and Cree community’s traditional territory in northeastern British Columbia. These wells abandoned by the fossil fuel extraction industry now represent an environmental risk for local residents, who saw scant economic benefit from the extraction of the crude oil that flowed beneath them.

But from those depths comes another chapter in Fort Nelson First Nation’s energy story, one that is green, and that it controls. Using royalties that the band office received from oil prospectors over decades, the community is now embarking on an entirely different transformation, looking to the future and developing a geothermal plant out of an orphaned oil well. It’s called Tu Deh-Kah, a Dene phrase that translates to “boiling water.” The First Nation hopes that the plant will go online in 2027, becoming one of Canada’s first electricity-generating geothermal facilities – and possibly the first one to be purely geothermal. Currently, the only large-scale plant is the dual natural gas and geothermal Swan Hills project in Alberta.

“We want to see a sustainable energy project in our territory that we own,” says Taylor Behn-Tsakoza, a community liaison officer with Tu Deh-Kah.

For Jim Hodgson, CEO of Deh Tai Corp., Fort Nelson First Nation’s economic development company, the project is steeped in pride.

Tu Deh-Kah is 100% Indigenous-owned and poised to generate seven to 15 megawatts, nearly enough to power the First Nation and Fort Nelson, the adjacent municipality of the same name.

Hodgson is an old-school oil and gas man who has worked in the industry for decades. Now, he is carrying over his expertise, and he’s not alone. Many in the First Nation have worked in the oil and gas sector, which Hodgson says gives them a skill set that transfers well to geothermal development. The burgeoning industry presents new opportunities for First Nations as the world drives toward an energy transition that leaves fossil fuels behind.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis people are already at the forefront of the energy transition in Canada, as partners in or beneficiaries of roughly 20% of the country’s electricity-generating infrastructure – virtually all in renewables. But oil and gas remains the largest private employer of Indigenous people in Canada, with 10,800 Indigenous workers, according to the most recent data from Ottawa.

As Indigenous communities around the globe forge transnational understandings of how to ensure that their interests are protected, can this renewable power help First Nations transition to the net-zero age?

The ‘whole moose’ approach

Tu Deh-Kah is not a traditional geothermal power-generating plant. For decades, geothermal has relied on the extreme heat of volcanic and high-temperature regions. But unlike the geyser-powered plants of Northern California or the volcanic heat of New Zealand, this project relies on a newer form of geothermal rooted in the sedimentary basin of Western Canada, which has traditionally housed rich oil and gas fields. “But there is a lot of heat in the earth,” says Jeremy O’Brien, the energy segment director for Seequent, a geoscience company that works closely with geothermal proponents to map the subsurface for geothermal projects.

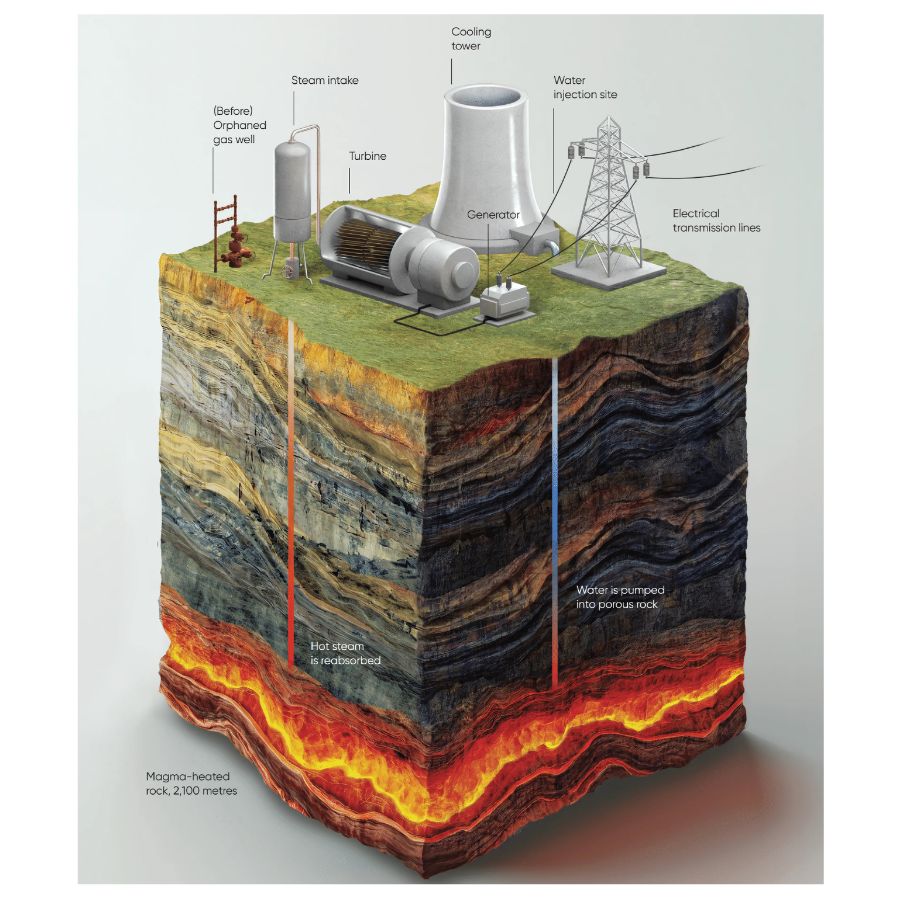

Geothermal power plants do not burn fuel to generate electricity; instead, hot brine is pumped from deep inside the earth and used on the surface as direct heat or to produce electricity. All told, the plants emit 97% less acid-rain-causing sulfur compounds and 99% less carbon dioxide than fossil fuel power plants of similar size, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Traditionally, geothermal projects in volcanic regions can run as hot as 250°C to 300°C. In contrast, Tu Deh-Kah expects its heat to operate between 107°C and 120°C. The lower heat means less power-generation efficiency, which is partly why projects on sedimentary-basin geological formations are lagging behind volcanic or geyser-based ventures. But O’Brien thinks there is an opportunity for oil and gas regions to transition to geothermal plants within basin regions. There is both expertise in drilling and deep knowledge of the subsurface, he says. “I think the technological crossover is really important.”

Tu Deh-Kah also carries the ethos of what Behn-Tsakoza calls the “whole moose” approach. “When we harvest the moose, we use everything; you would never even know we were there.”

We want to see a sustainable energy project in our territory that we own.

— Taylor Behn-Tsakoza, community liaison officer, Tu Deh-Kah

For example, the Tu Deh-Kah team plans to use the gas that remains deep in the old well to ensure that every element of the project is given a use, as if it were a moose. The First Nation is also exploring methods to extract lithium, a coveted critical mineral in the energy transition, from the brine, which it can then sell. And it has finished building a 2,000-square-foot greenhouse near the community’s school, Behn-Tsakoza says. It is the first of several that the First Nation plans to heat with the geothermal plant. The ambition is to grow enough commercial produce to “feed the North,” she says. Fort Nelson is an hour and a half south of the Northwest Territories border and on the transportation route to Whitehorse.

“Who knows what the future holds,” Behn-Tsakoza says. It’s a message she has tried to get across at dozens of community meetings, where she explains the project to local residents and receives their input and concerns.

Hodgson notes that the band office has held the project to the same standard that it would apply to any other company. “We don’t get it passed just because we’re owned by them,” he says. Band administrators conducted the required environmental and archaeological assessments and the project is now awaiting a final investment decision from the community’s council and membership. In February, the project received $1.2 million from Natural Resources Canada through the Indigenous Natural Resource Partnerships program, which is designed to increase the participation of Indigenous communities in the clean energy economy.

At the grocery store, Behn-Tsakoza sometimes runs into Elders who have their doubts about the project. “Has the project failed yet?” they’ll ask her. “Nope, I don’t think it’s going to,” she responds.

The reality is that geothermal in sedimentary basins remains relatively unproven on the continent. That has led to skepticism of the project’s viability, and its green credentials.

The Elders thought they had a “told-you-so moment” recently when project proponents discovered a lot more gas underground than expected. The former oil well extended approximately 1,500 metres into the earth; the geothermal project goes deeper, some 2,000 metres. But more sour gas remained deeper in the well than initially projected, and the geothermal project ran into it, raising an engineering and operational problem for the Tu Deh-Kah team, who are now figuring out what to do with it.

RELATED STORIES:

Indigenous knowledge keepers take their clean energy expertise abroad

Their land, their call: When economic reconciliation and climate justice conflict

Since the discovery, Behn-Tsakoza has been hearing it from Fort Nelson Elders at the grocery store. “See, this project isn’t going to be as clean as you think,” they say. “Whoa, whoa, whoa: our mission hasn’t changed,” she tells them – that is, to reap the benefits of a truly sustainable project. “Our vision hasn’t changed.”

Fort Nelson First Nation is not the only Indigenous community to cast its eyes to the promise of geothermal, though not without a strong sense of caution.

Jessica Eagle-Bluestone acts as an Indigenous liaison for Geothermal Rising, an international geothermal industry association. She says many tribal nations in the United States are “waiting to see if the technology improves more over the next couple of years” before venturing in. She says a lot of economic and structural risk remains with some old oil wells, depending on their integrity. But she believes there’s opportunity. While studying at the University of North Dakota, Eagle-Bluestone won a U.S. Department of Energy competition for developing a concept for a project to convert an old oil well in her home community in North Dakota into a geothermal plant. “It’s definitely on the radar of tribes,” she says.

O’Brien says that North American developers just need to look to Europe for successful sedimentary-basin geothermal developments. In Paris, geothermal is powering around 250,000 homes. In Munich, numerous geothermal plants provide a significant chunk of the city’s heating. “We see that potential starting to roll through,” he says.

The Dixie Meadows warning and the Indigenous geothermal declaration

Like any major energy project, geothermal development can fall victim to mistakes and the antipathy of Indigenous Peoples, often as a result of poor site selection and lack of meaningful consultation.

In Dixie Meadows, Nevada, a controversial geothermal project has led to court challenges from the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe and the Center for Biological Diversity. The project’s plant is proposed to be built on a spiritual site for the tribal nation, cutting off the community from the location that is home to their creation story. The site is also home to a unique species of toad that is at risk of extinction if the project goes ahead.

The main issue here has been a lack of meaningful consultation that incorporates the interests and values of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone. Scott Lake, a litigator for the Center for Biological Diversity, says that during the consultation there was an emphasis on “process over outcome,” which didn’t take the concerns of the tribe seriously. As a result, the community launched a legal challenge over concerns about the impact the project would have on its religious and historical site. “No one started out on a crusade against geothermal energy – it just happens to be right where they view their creation site,” says Lake, who is working with the Fallon Paiute Shoshone to litigate against the project. “I mean, it’s just a really terrible place [to put it], and that’s the issue we’re dealing with.”

For Lake, unless thoughtful decisions on site selection are informed by meaningful consultation and free, prior and informed consent, projects like the geothermal plant in Dixie Meadows will run up against opposition. He says the United States is behind other countries in upholding the spirit of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and its meaningful- and early-consultation principles. “At the end of the day, it’s an efficiency issue,” he says. “Do you want to push through projects that are going to get litigated and delayed, or do you want to find, you know, situations where there’s not as much conflict?”

Do you want to push through projects that are going to get litigated and delayed, or do you want to find situations where there’s not as much conflict?

— Scott Lake, litigator, Center for Biological Diversity

A bid to chart a better path forward emerged last year at the first-ever Indigenous Geothermal Symposium in Hawaii. Indigenous leaders in the geothermal space came together and developed the Geothermal Indigenous People’s Declaration. The declaration calls on the wider geothermal community to uphold UNDRIP, to consult early in the process and to ensure that Indigenous nations benefit from the project, while not compromising their duties as land stewards.

Aroha Campbell is a kaitiaki consultant and one of the leading voices in developing the declaration. Decades ago, she saw geothermal plants built across the Maori homeland without benefits to local communities. She has dedicated her career to changing that equation and has negotiated partnerships with geothermal developments that earmark funding for Maori community initiatives, including cultural camps and housing.

For Campbell, the declaration is a starting point for all Indigenous nations across the world wrestling with the potential and pitfalls of geothermal. Campbell believes each Indigenous nation can take the declaration to their homelands and place it on the negotiating table with developers. The hope is to help the industry understand what working with Indigenous nations on geothermal projects will look like. Until then, Indigenous nations must keep their networks among kin strong.

“I believe the best thing that could happen for Indigenous people in geothermal is sharing,” Campbell says. “The good and the bad, and that sharing of the stories in regards to the developers as well, and the likelihood that all of our stories are very similar.”

Matteo Cimellaro was the Indigenous affairs reporter for Canada’s National Observer, with whom this story is co-published. He now reports on the public service for the Ottawa Citizen.