For some celebrities, saving the world isn’t just an on-screen occupation.

In February 2021, Robert Downey Jr. appeared on The Colbert Report to prove he’s a superhero out of the Iron Man suit too. In the segment, he plugged his green advocacy and venture capital initiative, FootPrint Coalition, which works with start-ups aiming to disrupt dirty industries. In a bit of show and tell, Colbert and Downey Jr. joked about two of FootPrint’s planet-saving ventures, bamboo and bugs. After stroking his cheek with sustainable bamboo toilet paper, Colbert held up a jar of brownish powder and quipped, “You’re not just getting me to eat dirt, are you?”

The powder was a mealworm larvae protein made by French start-up Ÿnsect, which to date has secured US$375 million in funding. According to FootPrint, mealworm larvae and other insect feeds present a big opportunity to clean up the notoriously polluting aquaculture industry. With global fish consumption doubling in the past 50 years, the company says that feeding fish insects, instead of the typical sardines, anchovies and soy, requires 98% less land and cuts overall resource use in half.

“We’re doing something incorrectly,” Downey Jr. told Colbert. “If we make this switch, it’s a huge, huge intervention.”

Beyond aquaculture, the environmental case for humans replacing vertebrate protein, especially greenhouse-gas-intensive beef, with lower-emitting insect protein is compelling. A seminal 2013 report from the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) on eating insects highlighted the myriad benefits of edible insects, which include circular use of waste to rear insects, relatively low greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions, and low water use.

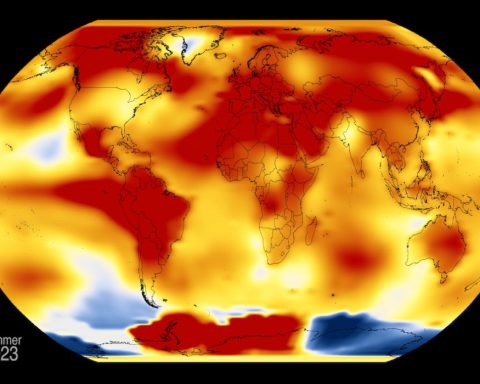

Given that agricultural, forestry and other land-use emissions account for 22% of global emissions, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development figures (nearly half of those are caused by livestock production), cutting food emissions while increasing food security is imperative. Combined with the nutritional case for insect protein (it’s packed with amino acids, fibre and micronutrients), and that it’s considered low risk for spreading zoonotic infections, deploying this supposed panacea seems like a cut-and-dried case to transform global food supplies.

But a potential blind spot hovers over the insect movement. Questions about insect sentience and welfare gather in the background, raising the spectre of a factory farming repeat, just on a miniature scale. Counterintuitive as it may seem to push pause on a potentially promising climate solution, the insect movement demands a deeper reflection on emission reductions that subjugate other life forms to mitigate a crisis caused by humans.

Swarms of investors

The business case for insect farming is strong, too. Conditions are ripe for growth, and investors are ponying up. Aside from venture-capital initiatives like Downey Jr.’s, government-backed insect mega-plants have been swarming agricultural news. In the last few years, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada awarded up to $8.5 million to a London, Ontario, cricket producer and $6 million to a facility in Alberta that breeds black soldier flies. In the U.K., a black-soldier-fly start-up won a £10-million grant from a government industrial-strategy fund to construct a facility outside London, while Ÿnsect snagged €20 million from the European Commission to build a vertical farm in northern France that would increase its production by 50 times. Earlier this year, a Spanish mealworm producer announced that it’s poised to break ground on a new facility that is reported to be the world’s largest at 90,000 square metres.

These facilities primarily produce animal feed and pet food, which is where most industrial insect production goes (for now). Even still, the output figures are staggering for an industry that remains somewhat marginal. A 2020 report from the research group Rethink Priorities estimated that upwards of 1.2 trillion insects are produced annually for feed and food (the majority being black soldier flies, crickets and mealworms), figures that would skyrocket with the mainstreaming of entomophagy – that is, humans eating insects.

Roughly two billion people worldwide already eat insects regularly (largely in Asia, Africa and Latin America). Most of this, however, is locally caught, harvested and consumed as an affordable, traditional source of protein and, often, a means of survival. On North American grocery shelves, they’re being branded as a novelty “superfood”: crickets are turning up in products like protein bars, chips, cookies and whole protein powders. The trend has been getting the full social media influencer treatment, making ripples on TikTok and Instagram with fitness buffs calling insect protein a game-changer in their regimens.

Still, as the industry marches forward and markets more directly to humans, a nagging question keeps coming up: is insect farming cruel?

Couldn’t hurt a fly?

To answer that, scientists are investigating the notion of sentience. Invertebrates have historically been considered insentient, but a growing body of research shows that it’s more complicated than previously thought.

Lars Chittka is a professor of sensory and behavioural ecology at Queen Mary University in London and the author of The Mind of a Bee. He has conducted and reviewed hundreds of experiments to observe cognition- and emotion-like states in bees and other insects. “The conventional wisdom about insects has been that they are automatons – unthinking, unfeeling creatures whose behavior is entirely hardwired. But in the 1990s researchers began making startling discoveries about insect minds,” Chittka writes in Scientific American. He points to ants rescuing nest mates buried under rubble and bumblebees seeming to experience joy, noting that “bees and other insects also form long-term memories about the conditions under which they were hurt.”

While there are no universally accepted criteria to determine invertebrate sentience, Chittka uses a framework developed by the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics. Jonathan Birch, associate professor and cognition researcher, recently led a five-year project called Foundations of Animal Sentience that devised eight criteria, which include exhibiting self-protective behaviour and whether an animal values an analgesic when injured. Birch’s work on sentience led to the inclusion of octopuses, crabs and lobsters (all invertebrates) in the U.K.’s Animal Welfare Act in 2022.

Of 20 insect producers and brands randomly selected by Corporate Knights, only four had public welfare statements.

Chittka, with other researchers, mapped hundreds of studies against Birch’s eight criteria and found, for example, that adult flies and mosquitos satisfied six, which indicates strong evidence of sentience according to Birch’s grading scheme.

Of course, establishing cows and pigs as sentient hasn’t prevented cruelty in factory farming, but Chittka notes it has led to legislation that pain and distress should be minimized.

“Science tells us,” Chittka writes, “that the methods used to kill farmed insects – including baking, boiling and microwaving – have the potential to cause intense suffering.” Other academics call for applying the animal sentience “precautionary principle,” also devised by Birch, which states that “where there are threats of serious, negative animal welfare outcomes, lack of full scientific certainty as to the sentience of the animals in question shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent those outcomes.”

Even if insect sentience becomes accepted by the industry, implementing rigorous welfare standards and metrics is complex and species-specific, researchers note, and likely to lag behind industry growth.

At this point, the industry is a wild west, and welfare measures are mostly voluntary. (Where regulations do exist, they mostly address food safety, not welfare.) Of 20 insect producers and brands randomly selected by Corporate Knights, only four had public welfare statements.

Ethologist Jonathan Balcombe, the author of Super Fly: The Unexpected Lives of the World’s Most Successful Insects, calls flies the entrepreneurs of the insect world, with a “fantastic diversity of expressions and behaviour.” On the notion of welfare, Balcombe tells Corporate Knights, a move toward insect consumption may be the lesser of two evils and preferable to the factory farming we have now.

“If they can make major dents in conventional factory farming of vertebrates, that is a good outcome.” However, “it’s a grim scenario,” he notes, “if insects turn out to be highly sentient or sentient at any level.”

It’s a grim scenario, if insects turn out to be highly sentient or sentient at any level.

—Jonathan Balcombe, author, Super Fly: The Unexpected Lives of the World’s Most Successful Insects

It may be a trap we’re setting for ourselves. Balcombe says the insect industry “assumes a growth economy, which is a dead end we ultimately need to move away from.” In Downey Jr.’s video for FootPrint Coalition flagging insects as climate-friendly fish feed, he does not suggest that humans eat less fish. Asking consumers to cut back has always been a delicate issue in the climate movement; instead, the movement often looks for solutions that can support current consumption levels.

In the end, we just seem to get more factory farming, bringing up a question larger than how to make insect farming more humane: is now the time to ditch factory farming altogether?

Cold, hard climate math

With the Paris Agreement’s target of net-zero by 2050 fast approaching, economies are scrambling to transition to, and cement, the practices that will make up the next green industrial age. Coal mining and internal combustion engines will be a thing of the past. Does factory farming trillions of insects have a place among EVs, solar-powered homes and plant burgers? If the answer is no, supplanting entrenched industries is no small feat, and we have a small window to course correct.

“If we realize insects are sentient,” Balcombe says, “it’s more difficult to upend or end an industry that already has a foothold.”

Human–insect relations have historically been fraught with ambivalence, ranging from reverence to disgust. For ancient Egyptians, scarab beetles represented the eternal cycle of life. Jain ascetics, to avoid harming insects, gently sweep the ground in front of them as they walk. In some homes, centipedes are treated to glue traps and ants are poisoned. Cochineals give us “carmine” red pigment for food colouring and cosmetics. And, of course, bees are vociferously defended by environmentalists for the indispensable pollination they provide, which gets to the heart of how we came to farming more than a trillion insects a year: their status is determined by what they can do for us.

This approach corresponds to a mindset of solving climate change that is absent a wider appreciation for why life on Earth is worth saving in the first place. Creatures that can provide utility in cutting emissions are folded into the industrial machine and heralded, in the case of powderized crickets, as a cleantech innovation, even if the process entails suffering and the deprivation of a life in a natural habitat. It’s still factory farming, only this time it’s low carbon. Call it a kind of cold, hard climate math.

If the climate movement takes an intrinsic-value approach to insects, it may steer away from industrial-scale insect farming and embrace less morally grave alternatives that still lower greenhouse gases and boost food security. No, not certified free-range organic insects, but other innovations racing to solve agriculture’s climate problem, such as plant protein and cell-based meat.

Ultimately, it will be consumers who decide. If the insect craze amounts to crickets, it would be one time Iron Man didn’t save the world.

Christopher St. Prince is a Toronto-based journalist and fiction writer.